Folate-dependent Hypermobility: Discussing Tulane’s Recent Paper With Their Scientists

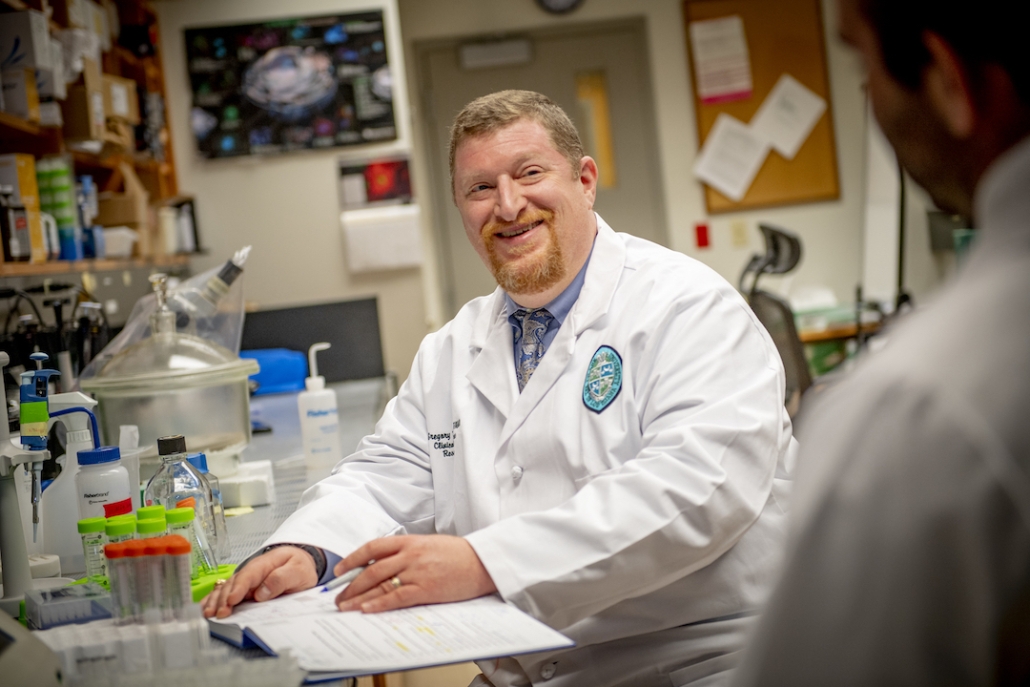

A recent publication by researchers at Tulane University hypothesizes MTHFR mutations lead to folate deficiency, resulting in hypermobility. The researchers also propose these mutations may cause or contribute to a form of hypermobile EDS. Journalist Karina Sturm spoke with Jacques Courseault, physical medicine and rehabilitation and sports medicine doctor at Tulane’s Hypermobility and EDS clinic, as well as with Professor Gregory Bix, Director Clinical Neuroscience Research Center. The researchers explain their hypothesis and how it may relate to hypermobile EDS, share potential treatment options, and their future plans to prove the proposed mechanism.

Karina Sturm: Hi, everyone. I am so glad we got to connect. Thanks for making the time to speak with me today. First, can you introduce yourself briefly and tell me a bit more about your EDS clinic?

Jacques Courseault: My name is Jacques Courseault. I’m a physician at Tulane University, specializing in physical medicine and rehabilitation, and I have a subspecialty certification in sports medicine. I do a lot of injection-type treatments for athletes but also for non-athletes for pain issues, such as neck and back pain, but I focus on all issues from head to toe. Tulane is a major academic center where we got more and more referrals for patients with known Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. However, we learned about it for three minutes in medical school. So I did not know much about it beforehand. At some point, I realized that there was a pattern in my patients. I saw patients with EDS who had dysautonomia and mast cell issues, and those seemed to overlap with other patients who came in with complex pain. When we asked those patients if they got lightheaded when standing up or menstrual issues and allergies, they all said, “Yes.” So I had to ask myself, “Are both those groups having the same diagnosis, hEDS, but one simply hasn’t been diagnosed yet? “I started sending those undiagnosed patients to geneticists, and they confirmed they all had hypermobile EDS or were at least somewhere on the hypermobility spectrum. We also realized when we sent them out to existing EDS clinics that there were not many around, which made us decide to start our own. Thirty minutes after posting on the Facebook page about the new clinic, we were booked for six months.

Sturm: (Laughs). Yeah, that’s unsurprising.

Courseault: We quickly realized the vast need. Now, we’re three years into it, learned a lot, and are very busy. So this was my long introduction. (Laughs).

Greg Bix: Well, mine will be shorter. (Laughs.) I am Greg Bix. I’m a professor of neurosurgery and neurology here at Tulane. I run a clinical neuroscience research center, so I’m a translational neuroscientist, but my background is in connective tissue and the extracellular matrix. When Jacques realized there might be something interesting going on in his patients, he reached out to me because, in the past, I’ve published on decorin and other extracellular matrix molecules. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Courseault: And we’ve been collaborating ever since.

Sturm: Let’s talk a little about that publication of yours. I read the paper as well as the press release, but they didn’t a hundred percent line up. Your paper seems to be a hypothesis without patient data, right? Can you tell me a little about the paper itself, what hypothesis you are proposing, and how you came up with this hypothesis?

Courseault: It started with clinical observation. I am an MD, so I was not too interested in biochemistry and genetics, to be honest with you, but now that’s what I’m spending my days in life doing. (Laughs). I started doing tons of research and tried to learn all I could about hypermobility and EDS and the reasons why my patients are hurting or what causes them fatigue or blood pressure issues. I wanted to identify a cause. So we looked at a battery of blood tests from over a thousand patients – more than that at this point – realizing that there was a pattern, particularly with high folate levels that were really through the roof. I asked other hematologists and biochemical experts, and geneticists to find out whether those findings were relevant, but everyone said it was benign. However, the hypermobility EDS population is very involved in their medical care. I’ve learned a lot from my patients. A lot of them had MTHFR testing in addition to other genetic tests, and many did have these MTHFR polymorphisms. So while I was permanently told in medical school these mutations are not serious, it just did not add up because we saw these high folate levels. That’s when I took my clinical limitations and sought out Dr. Bix, who’s spent decades studying this. I asked him if folate or the enzymes involved in folate metabolism might be interacting with collagen or extracellular matrix proteins. It just so happened that he researched decorin, so we were able to further dig into folate research and put together the hypothesis. I’ll pass the ball on to Dr. Bix to further explain the biochemical process.

Bix: I’ll try my best. I completely agree with Jacques on that. The paper itself is a hypothesis, but it’s based on clinical evidence. It’s based on what he’s seeing in the majority of his patients coming in. When a majority of your patients have very similar trends in their values, in this case, folate, there’s something there. So we basically put these ideas together based on what we were observing clinically. Right now, we’re hard at work putting together the follow-up paper where we actually present the hard numbers.

Sturm: I was hoping that you would have data to prove this.

Bix: As scientists, sometimes you have such a great idea, you really just want to get it out there because it may benefit a lot of people. But then we want to follow that up with the facts, with the numbers, so to speak.

Sturm: Can you give me a spoiler of how many people we are talking about? How many patients did you see with these mutations?

Courseault: You know, the MTHFR polymorphism prevalence [in the general population] is about 35 %, and, spoiler, in our clinic, it’s significantly higher than the general population

Sturm: Wow, that’s a lot. Your paper describes folate-dependent hypermobility, right? But you also mention it leads to a type of EDS and at the same time, you speak about benign joint hypermobility, which is not hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. How can you distinguish if folate-dependent hypermobility is EDS or if it is just a coincidental finding, which has nothing to do with EDS?

Courseault: EDS is really interesting. It’s been studied for centuries. To my surprise, in 200 years, medicine hasn’t progressed much. When genetic testing came out, only then were we able to distinguish between all those collagen-based disorders. However, in our clinic, we also realized we had a lot of very flexible patients with dysautonomia and MCAS. A huge majority of the EDS population is somewhere on the hypermobility spectrum, but in my experience, clinically, those patients are all treated differently – one hypermobile EDS patient is not going to be the same as the one standing next to him or her. So we see a lot of variations under the hypermobility umbrella that need to be specified. And the area we are looking at is those with MTHFR polymorphisms and folate dependency, which is great for us because it can be treated. Will it solve all problems with EDS? Not at all. But if we can identify an area that can clearly be diagnosed with testing and then treated with a pretty innocuous treatment, it is a huge win for medicine. Now, certainly, there are other interesting areas within the hypermobility umbrella, for instance, the gene Tenascin XB. We see a lot of patients with TNXB mutations.

Sturm: I have a heterozygous mutation on that gene, so I would be very interested in that research. Would you please do that for me? (Laughs).

Courseault: It’s an extracellular matrix protein, so it is in our wheelhouse. (Laughs). Then there’s hereditary alpha tryptasemia, which causes high tryptase levels, an enzyme that breaks down connective tissue. So those are early well-defined areas of hypermobility, but we also have patients that are MTHFR negative, Tryptase negative, and TNXB negative and still hypermobile. So there are a lot of puzzle pieces still to put into play, but breaking it up does help with research and treatment. And certainly, some have a combination of two or more. We’ve certainly seen patients with MTHFR and Tenascin XB mutations, which means we need to be more creative with our treatment plan. I think what we’re doing has a lot of significance in bringing further definitions to hypermobility.

Sturm: I think what confused me was that the press release framed the MTHFR mutations as if they were the cause of hEDS. I was wondering how you can be sure that mutations a large portion of the population has are the reason for hypermobility, or are you saying they’re only contributing to hypermobility due to folate?

Courseault: Folate is really important for congenital development. The Western world supplements folic acid in all foods to prevent neural tube defects. However, a subset of the population can’t process folic acid. They process it well enough to the point that they don’t have major neural tube defects, but we see congenital anomalies in the hypermobile population that are not seen in those that are non-hypermobile. So what is causing that? Is it folate? Probably. Do we need to further research that? Yes, absolutely. We do not know if there’s something to that, but that’s why we’re jumping into this. MTHFR variants are common: they are found in at least 35 percent of the population. How common is hypermobility [in the general population]? Probably 60%, you know. Now, EDS is much rarer; systemic manifestations are rare, but hypermobility is really common. We cannot say one causes the other for sure. One advantage we have is in our microcosm of collaboration with clinics and research here, we’ve been able to treat a lot of patients that are reporting benefits. So we do have a couple of things to prove, but for the benefit of humanity and because we see people suffer every day, we shared a hypothesis with a possible treatment that is safe and might help somebody.

Sturm: But to clarify, you are saying MTHFR mutations may cause hypermobility but not necessarily EDS, right?

Courseault: It depends. There are 13 subtypes of EDS. So the EDS are a very broad spectrum. You can test for all of them genetically, despite hEDS. I’m not saying by any means that folate metabolism issues cause a collagen genetic defect, but the majority of Ehlers-Danlos patients are hypermobile subtype. And then you have to break that down to see what’s causing those hypermobile subtypes. I am unsure if benign joint hypermobility exists because when you ask those seemingly “asymptomatic “patients if they get lightheaded every time they get up, they say yes. They’ll continue to tell you they have heavy menstrual cycles but always thought all of it was normal. So usually we find systemic manifestations for them if we dig deeper, but you won’t find this in a textbook because it’s not proven. EDS is really complex. And I think we’re just adding information to the pool, to open up resources and to bring more clarity to a very complex subject that people have been studying for centuries.

Sturm: Do you think there are several different genes involved with hypermobile EDS or environmental factors?

Courseault: I think so. What we are trying to do is to identify the causes, so we can better treat the patients, and it won’t be so confusing what hypermobility is.

Sturm: So let’s talk about that treatment. You treated all your patients with MTHFR mutations, right? What was the outcome?

Courseault: Yes, 5-methylTHF is the standard. It should be pharmaceutical grade, in our opinion. To me, it doesn’t matter which brand you use as long as it’s a high-quality brand. We are somewhat titrating based on the variant subtype. There’s no science that says what you need to take. Probably the best general recommendation is to start slow because there are people that do have adverse reactions to methylation. We have theories of why that might be. I think another broad-spectrum area of research is to figure out if there are some other genetic variants that can cause methylation issues. If you’re taking any methylated folate/methylated B12, maybe start with half a capsule for a week and then go up to a capsule and then go to half of the maximum daily value. All of this should be done under physician guidance and shouldn’t be just randomly started on your own because even though it’s very safe if people have an adverse reaction, they need medical oversight to make sure there’s nothing else going on. For people that don’t tolerate the methylated folate, we’ll move to folinic acid, which seems to be better tolerated than methylated folate. We do also treat with methylated B12 too because we have seen other polymorphisms that might be related – another pathway of research. It usually takes about four to six weeks, and people will message us and say, “I have more energy, my stomach is better, my mast cells are better controlled, and my dysautonomia and pain are improved. “Is it 100% fix? No, but we are seeing a greater than 50% improvement in most people.

Sturm: Wow. That’s a pretty huge number. Are there people who get worse?

Courseault: A few people have a bad reaction to methylation for whatever reason that I think needs to be looked into. Once we stop the supplement, people go back to baseline. It’s not a one size fits all for anyone because, again, EDS is complex. It’s not just extracellular matrix; it’s all these other things that are associated with it that you have to treat too. It’s still a very complex area of clinical medicine that needs to be managed by a multidisciplinary team or someone who really understands the different facets of hypermobility.

Sturm: What was the reason for you to start testing for folate in the first place?

Courseault: Folate and B12 are implicated in chronic fatigue syndrome and in polyneuropathies. A lot of our patients have high MCVs, which are large red blood cells that usually indicate B12 and folate deficiency. A good majority of our patients have high homocysteine levels, which is indicative of B12 deficiency. So we just put all those together.

Sturm: Can you give me a spoiler of what you plan in the future in terms of EDS research?

Bix: So, fortunately, in the lab, we can model a lot of these genetic polymorphisms, and we know quite a bit about decorin. You can think of decorin as the molecular nails that anchor collagen fibers. So when decorin is not processed normally, the connective tissue is abnormal, and that could contribute to the hypermobility that many of these individuals have. We can model this in animals and in cell cultures, and we can even therapeutically intervene with methylated folate and other things. So we can demonstrate in the lab whether or not these connections that we hypothesized are valid. That is work that’s actively ongoing. We’re going to follow up the hypothesis with the hard data.

Sturm: When do you plan to publish the data? Do you already know?

Bix: As soon as possible, for sure. But we’re also at the mercy of the editors and journals.

Sturm: You did also talk about Tenascin XB and other genes that might be involved in hypermobile EDS. Do you have plans to do some research on those as well?

Bix: Eventually, yes.

Sturm: Well, please call me if you do. Because I have a very high interest. (Laughs).

Is there anything important you would like to add regarding your research?

Courseault: I’m really impressed with the EDS hypermobility community. I’m very fortunate to be a part of a team of people that can help the EDS community feel better. These patients have so much tenacity. Even though they have seen many doctors, they haven’t given up. They do their own research, come extremely organized with binders, and know their medical history well. I’ve learned a lot through the years from a lot of these patients. I would say, “Don’t give up.” I think we’re onto something big here amongst many different avenues that can help. And hopefully, we can come up with good diagnostic criteria across the board and treatment plans for a disease that people don’t understand, and that’s not well taught in medical schools. Granted, it’s years of research, but I think here at Tulane and across other research centers, there’s a renewed interest in EDS and an understanding that this affects a lot of people. And the sooner that we can put together plans and options, the better people feel on a global scale. So hang in there, keep being tough, and you’re not forgotten.

Sturm: Thanks so much. I really appreciate all you’re doing.

Courseault: Thanks for your interest, Karina.

Bix: Yes, thanks!

All images contributed by Tulane University.

You may also want to read the news article related to this interview:

This interview was first published as part of our May 2023 newsletter here: https://www.chronicpainpartners.com

Karina Sturm

May 2023

Frank Marx

Frank Marx

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!